India Street

Katy West

India Street in the Vale of Leven, West of Scotland, is a charming terrace that backs onto a derelict factory site. This site was once the home to a global textile industry, Turkey red, whose main market was India.

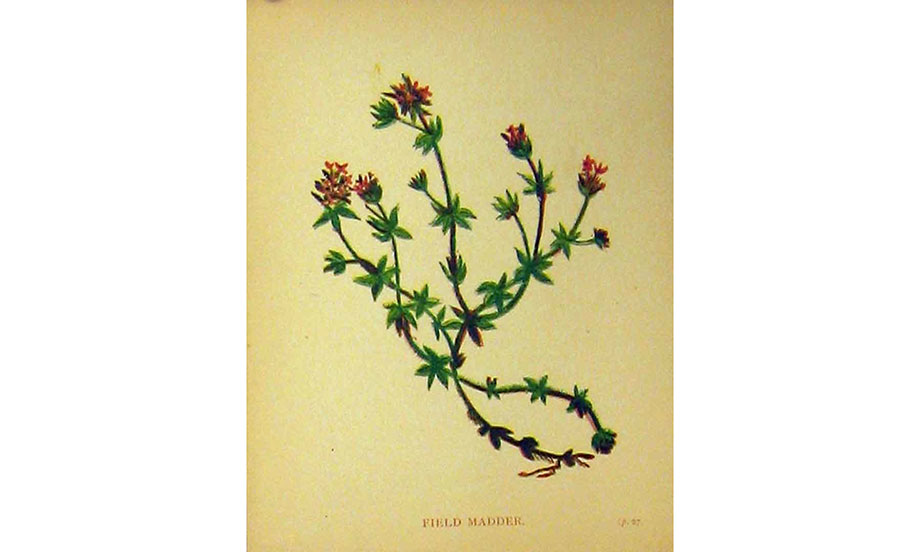

Turkey red is the name given to a naturally dyed cloth; a foul, costly and complex process involving extracting red dye from the madder root. As well as brilliant, cloth dyed with Turkey red was extremely durable and did not fade in water or light.

A Glaswegian businessman, George Mackintosh, invited a French chemist Pierre Jacques Papillon to Scotland and showed him a dyeing process that he had come across in Turkey. Together with industrialist David Dale they set up Dalmarnock Works in 1823.

The combination of hard, pure Scottish water, good infrastructure (thanks to the mighty Clyde) and rural land on which to develop a complex of factories and housing, all contributed to the suitability of the Vale of Leven for this industry.

Dalmarnock Work’s first products were polka-dot handkerchiefs, made by masking and bleaching the red fabric. These scarves imitated earlier bandana imports from Bengal, a name deriving from bandhani, an Indian tie-die technique. As the industry developed from handkerchiefs to bolts of cloth, Turkey red exported all around the world, producing designs that emulated the indigenous textiles of their intended markets.

Early printing methods were block, but soon industrial innovations developed a copper roller system that was faster and cheaper by which to print. Discharge dyeing was common practice. The red cloth was brought through steel plates with cut pattern, masking and revealing areas to be bleached, with details then added by Pencillers.

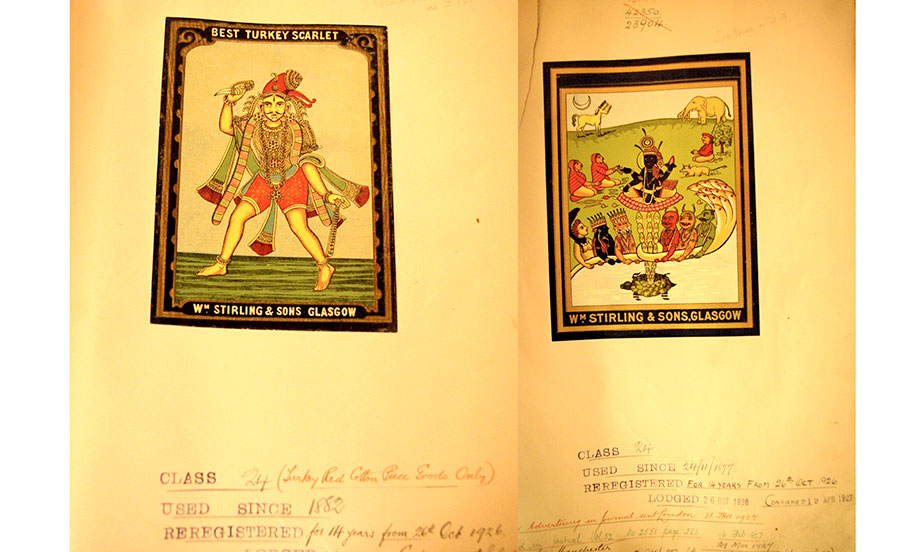

A number of competing manufacturers began to spring up in Dunbartonshire. The products were exported to India and the parcels distinguished by their labels, with designs to rival the fabric itself. Rival companies would come to blows over licenses, not for fabric, but regarding forgery of the export labels that would distinguish their products on foreign wharfs.

There was heavy competition between the companies in Glasgow. They strove to capture international markets and keep up with changing fashions, producing new designs on a monthly basis. Many issues arose over copyright and the companies worked fast to patent their designs. The patent however would only lasted a few months before lapsing, and a rival could copy that design.

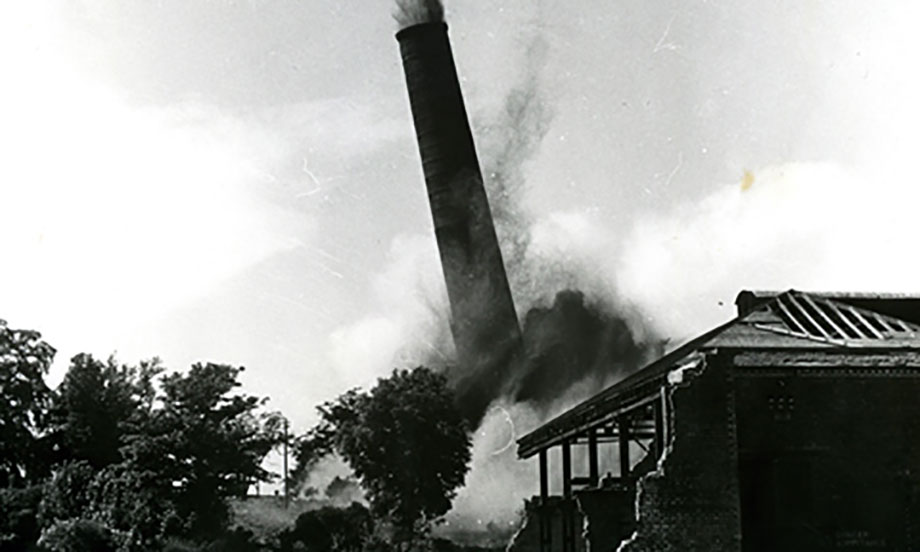

To make business even harder, in 1869, Alizarin, a new simpler artificial dye, was developed in Germany. The companies who had once been bitter rivals all joined to form the Turkey Red United Co. LTD in a bid to remain in business. Their focus was on the increased competition coming from India and the measures that were coming into practice in the form of heighted import duties, greatly affecting their profits and sales.

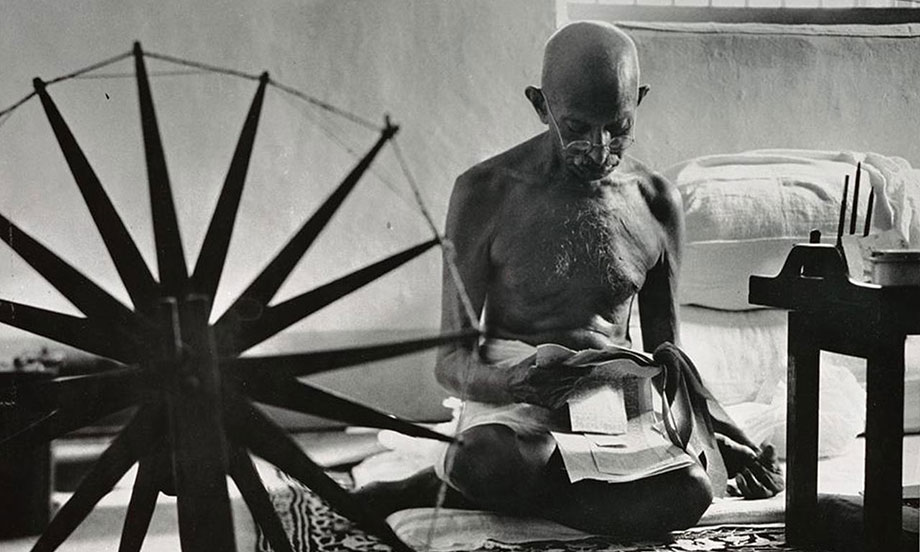

In 1905, with the partition of Bengal (now Bangladesh and West Bengal) a peaceful movement was established to support the demand for Home Rule in India. Swadeshi was a non-violent economic strategy aimed at removing the British from power, which included boycotting British products and the revival of domestic production.

The success of Swadeshi contributed to the end of the Turkey red in Dunbartonshire. Along with the dwindling Indian markets, changes in fashions, and cleaner, artificial, dying-techniques that gradually replaced the laborious Turkey red process, the industry was in decline in the 20th century until the last factory shut its gates in 1960.